Mattia Balsamini is an italian photographer who found his voice by capturing the surreal glimpse of science and society. His journey into the world of photography is filled with interesting subjects and researches. His photos inspire and make you take another look at what’s happening around us. With meticulous attention to lighting and details, his recent project (Protege Noctem, if darkness disappeared) wants to rise awareness on the effects of light pollution.

Mattia Balsamini è un fotografo di Pordenone che ha trovato la sua voce catturando il surreale nella scienza e nella società. Il suo viaggio nel mondo della fotografia è costellato da soggetti e ricerche interessanti: le sue foto ispirano e illuminano ciò succede attorno a noi. Con grande attenzione alla luce e ai dettagli, il suo recente progetto (Protege Noctem, se la notte scomparisse) vuole sensibilizzare sugli effetti dell’inquinamento luminoso.

Tell us a little about your training: are there things you would have done differently?

Raccontaci un po’ della tua formazione: ci sono cose che avresti fatto diversamente?

When I decided to pursue a course of study in professional photography, I did so because I was very attracted to commercial photography, with the purpose of conveying an object, a message. I was attracted to the aesthetic formality of photography and its functional potential. I studied in a “technical” school in the United States, and then went on to work as an assistant and image archivist in various advertising photography studios.

Over the years, slowly, things changed and I began to see photography as a softer, even introspective, medium of expression. I have enjoyed and observed a lot of photography since I was a kid, but my regret is perhaps that I did not realize earlier in my career how much even my own of photography could convey and represent some kind of sentimental connection.

Quando ho deciso di affrontare un percorso di studi nella fotografia professionale l’ho fatto perchè ero molto attratto dalla fotografia commerciale, con lo scopo di veicolare un oggetto, un messaggio. Ero attratto dalla formalità estetica della fotografia e dalla sua potenzialità funzionale. Ho studiato in una scuola “tecnica” negli Stati Uniti, e sono passato poi al lavoro di assistente e archivista di immagini in vari studi di fotografia pubblicitaria.

Negli anni, con calma, le cose sono cambiate e iniziato a vedere la fotografia come un mezzo espressivo più morbido, anche introspettivo. Ho fruito e osservato molta fotografia sin da ragazzino, ma il mio rimpianto è forse di non aver capito prima nella mia carriera quanto anche la mia di fotografia potesse veicolare e rappresentare un qualche tipo di connessione sentimentale.

What can’t photography do?

Che cosa non può esprimere la fotografia?

There are aspects of the human experience of the world that photography has a harder time conveying, but I don’t think there are some that are totally precluded from it. I think it depends a lot on the author/author. I have images in mind where the sense of place, the atmosphere, the thrill of feeling inside a situation is as strong as being or having been in the place photographed.

This happens to me with the images of less composed, more visceral and less scholastic authors. In my case, however, I am not sure what I am able to convey. What I inevitably feel as an ingrained characteristic and not very unhinged despite various technical contrivances, is the feeling of stability, of reduced dynamism that photography has, compared to video. But I see it as a plus, a more established and iconic force.

Ci sono aspetti dell’esperienza umana del mondo che la fotografia fa più fatica a veicolare, ma non credo che ce ne siano di alcuni totalmente ad essa preclusi. Credo dipenda molto dall’autore/autrice. Ho in mente immagini in cui il senso del luogo, l’atmosfera, il brivido di sentirsi dentro una situazione è forte come essere o essere stati nel luogo fotografato. Mi succede con le immagini di autori meno composti, più viscerali e meno scolastici. Nel mio caso invece non sono sicuro di cosa sono in grado di trasmettere.

Quello che inevitabilmente sento come una caratteristica radicata e non molto scardinabile nonostante vari escamotage tecnici, è la sensazione di stabilità, di ridotto dinamismo che ha la fotografia, rispetto al video. Ma la vedo come un plus, una forza più consolidata ed iconica.

Many of your projects focus on science and technology issues, can you tell why?

Molti dei tuoi progetti si concentrano su tematiche scientifiche e tecnologiche, come mai?

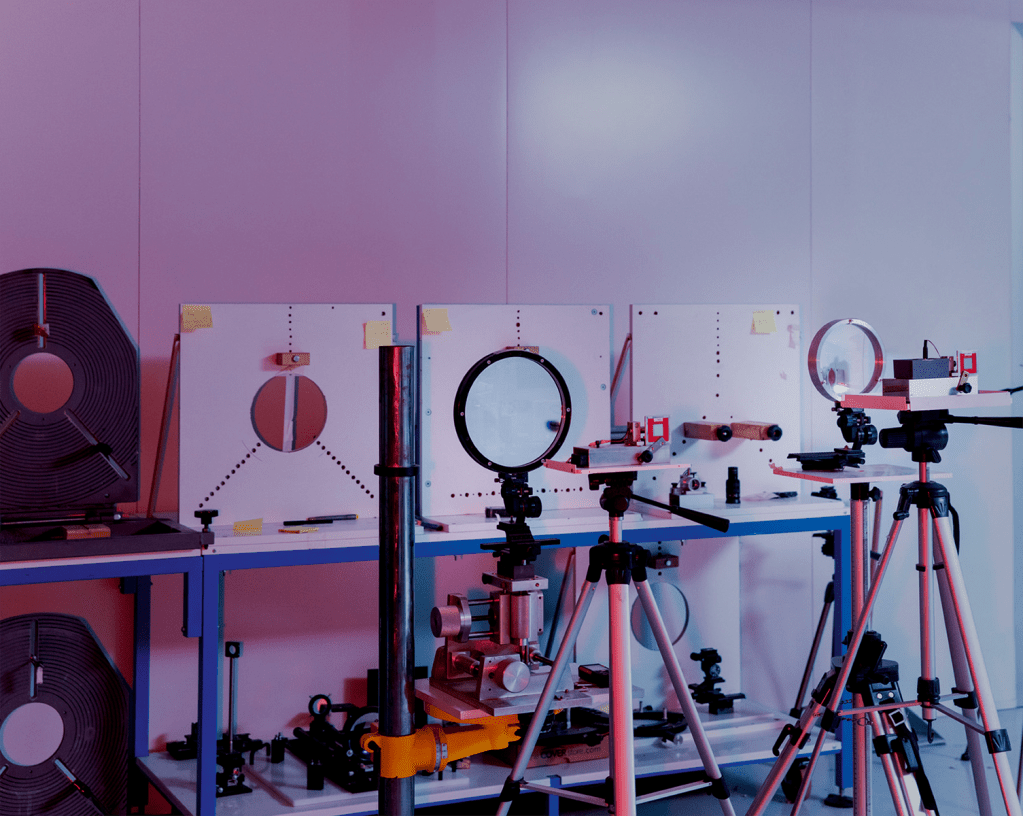

I have an idea of photography that straddles the functional and the surreal. The practice of photography is simultaneously a means and an end; I aspire to create informative and didactic images with respect to the leading themes of my research on technology, trying to make sure that taken individually they can live on some intangible suspended magic.

It is a desire that stems from my view of all things, a fascination I have had since childhood-perhaps from the perverse attitude of wanting to understand, but not all the way through, otherwise that magic might perhaps disappear. Work, technique, technology for represent an action, but also a place, a space in which we move and exist. I think I deal with these themes to rediscover what I first saw in my childhood.

Ho un’idea di fotografia a cavallo tra il funzionale ed il surreale. La pratica fotografica è contemporaneamente un mezzo ed un fine, ambisco a creare immagini informative e didattiche rispetto ai temi portanti della mia ricerca sulla tecnologia, cercando di fare in modo che prese singolarmente possano vivere di un qualche impalpabile magia sospesa. È un desiderio che deriva dalla mia visione di tutte le cose, una fascinazione che ho sin da bambino – forse dal perverso atteggiamento di voler capire, ma non fino in fondo, altrimenti quella magia potrebbe forse scomparire. Il lavoro, la tecnica, la tecnologia per rappresentano un’azione, ma anche un luogo, uno spazio in cui ci muoviamo ed esistiamo. Credo di occuparmi di questi temi per riscoprire ciò che ho visto per la prima volta nella mia infanzia.

You also do portraits, what do you usually look for in subjects?

Ti occupi anche di ritratti, cosa cerchi nei soggetti di solito?

The shapes, the suspension of the moment, their attention but also their temporary bewilderment. With the ambition to create a suspended space between me and them that is read as unique.

Le forme, la sospensione del momento, la loro attenzione ma anche il loro smarrimento temporaneo. Con l’ambizione di creare uno spazio sospeso tra me e loro che venga letto come unico.

“Protect the night (if the night disappeared)” is a very engaging invitation (and a threat), can you tell us about your latest project?

“Proteggere la notte (se la notte scomparisse)” è un invito (e una minaccia) davvero molto coinvolgente, ci vuoi parlare del tuo ultimo progetto?

For all of us, blinded by the shards from billions of artificial lights (or ALAN: Artificial Light At Night), the night sky has become a soiled canvas, an unknown phenomenon. Eighty-three per cent of the world’s population has never seen the Milky Way, the galaxy we call home. And in cities like Shanghai, where the world’s largest astronomy museum recently opened, ninety-five per cent of the stars are now in fact invisible to the naked eye.

Public lighting, windows, street lamps and even LED headlights emit blue spectrum light that dazzles the nocturnal ecosystem and damages the human circadian cycle, our endocrinal interplay of sleep and wakefulness, promoting the simultaneous onset of diseases such as breast and prostate cancer, diabetes and depression.

Epidemiologists are united in considering the disappearance of the night as a risk factor on a level footing with pollution, alcohol and smoking. “We call on the Commission to put into place an ambitious plan to significantly reduce the use of outdoor artificial light by 2030,” wrote the European Parliament in alarmed tones, in its document titled Biodiversity Strategy 2030: Bringing nature back into our lives.

It’s not only light on Earth but also up there: the proliferation of telecommunication satellites creates false cosmic streaks that prevent astronomers from studying the celestial vault. And natural life itself appears to have been harshly affected: migratory birds veer off course, plant leaves no longer sense the onset of winter, and many insects face extinction: this is why defending the darkness represents the vanguard in the ongoing ecological battle to avert apocalypse.

Protege Noctem is a documentation project chronicling the unofficial alliance between scientists and citizens to counter the disappearance of the night and its creatures.

È un progetto a cui ho lavorato con il giornalista Raffaele Panizza. Per tutti noi, accecati dalle unghie di miliardi di luci artificiali (ALAN: Artificial Light At Night), il cielo notturno è diventato un telo sporco, un completo sconosciuto. L’83 per cento della popolazione mondiale non ha mai visto la Via Lattea, la galassia che ci ospita. E in città come Shanghai, dove è stato inaugurato il più grande museo astronomico del mondo, il 95 per cento delle stelle ormai è invisibile a occhio nudo.

Le luci pubbliche, le finestre, i lampioni, persino i fari a LED, emettono uno spettro blu che abbaglia l’ecosistema notturno e danneggia il ciclo circadiano dell’uomo, la sua danza endocrina di sonno e di veglia, favorendo lo strisciare contemporaneo di malattie quali il cancro al seno, alla prostata, il diabete, la depressione.

Gli epidemiologi, compatti, considerano la scomparsa della notte come un fattore di rischio pari dell’inquinamento, all’alcol e al fumo. Il proliferare di satelliti per le telecomunicazioni crea false strisce cosmiche che impediscono agli astronomi di compiere studi sulla volta celeste. E la vita naturale appare compromessa: gli uccelli migratori perdono le rotte, le foglie non sentono più l’arrivo dell’inverno, gli insetti vanno incontro all’estinzione: ecco perché difendere il buio, scongiurarne l’apocalisse, rappresenta l’avanguardia della battaglia ecologica in atto. Protege Noctem è un progetto di documentazione che racconta l’alleanza carbonara tra scienziati e cittadini per contrastare la scomparsa della notte e delle sue creature.

Nel suo libro, Elogio del Buio, Johan Eklof sostiene che il bisogno di luce sia l’elemento distintivo dell’antropocene; pensi che questa nostra megalomania possa essere invertita in qualche modo o siamo destinati all’autodistruzione?

In his book, Praise of the Dark, Johan Eklof argues that the need for light is the distinctive element of the anthropocene. Do you think this megalomania of ours can be reversed somehow or are we doomed to self-destruct?

In part we are already doing this, albeit at a pace and with efforts that are less than the extent of the damage. I am aware that as humans we have self-destructive tendencies, but I want to be hopeful about our chances of succeeding. In the projects I have been involved with in recent years, I have seen many reasons to be.

In parte lo stiamo già facendo, anche se a un ritmo e con degli sforzi minori rispetto all’entità dei danni. Sono consapevole che come umani abbiamo delle tendenze autodistruttive, ma voglio essere speranzoso rispetto alle nostre possibilità di farcela. Nei progetti di cui mi sono occupato negli ultimi anni ho visto molte ragioni per esserlo.

Are you afraid of the dark?

Ma tu, hai paura del buio?

Forgive the light note to evade your question: a dear friend often points out to me that one is not afraid of being alone in the dark, but of not being alone.

Perdonami la nota leggera per eludere la tua domanda: un caro amico mi fa spesso notare che non si ha paura di essere da soli al buio, ma di non esserlo.

MATTIA BALSAMINI

mattiabalsamini.com

IG: @mattiabalsamini