What happens when the promise of the future crumbles, and the present takes on the contours of a labyrinth we traverse distractedly? What are the effects of a past that, seemingly boundless, appears to suffocate the window of the present?

These and many other questions were explored by philosopher Mark Fisher (United Kingdom, 1968–2017), whose reading of history—its disturbances and symptoms—serves as an excellent tool for navigating the present.

In his main essay, Capitalist Realism (2009), the critic frequently references concepts such as the slow cancellation of the future (Franco Berardi) or the end of history (Francis Fukuyama). These claustrophobic expressions convey the profound sense of despair that arises from living in a system whose destiny seems already written, and against which it appears almost impossible to propose alternatives. This is the idea encapsulated in the opening line: “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism,” with which his magnum opus begins.

With capitalist realism, Fisher refers to a system—or rather, an “atmosphere” (2009)—that does not proclaim itself as a paradisiacal state but convinces us that it is the best solution to contemporary problems. In this framework, seeking alternatives is seen as nothing more than a waste of time, a manifestation of naïve utopianism. Faced with this theft of imagination and hope, it is easy to understand the pervasive sense of loss and unease.

THE MENTAL CRISIS OF REALISM, BETWEEN ANXIETY AND SOCIAL MEDIA

It is no coincidence that mental illness occupies a central space in Fisher’s work. In particular, the philosopher insists on the need to analyze in greater depth the causes of conditions generally considered “secondary,” such as anxiety. For having personally experienced the grip of anxiety, Fisher denounces its broader culprit: capitalism. Anxiety and depression appear as human, natural reactions to the devastation wrought by the system—a machine that cares for nothing but what fattens it.

But There Is More. This sense of satiety is not merely a characteristic of the ruling class; on the contrary, it is the very tool through which it has learned to dominate with unparalleled mastery. Proof of this lies in our morbid relationship with technology and, above all, with social media.

Screens that mesmerize us with their violent glow. Vortices of data and carousels of banality that—zombifying us—soothe our distress.

This is what Fisher calls “depressive hedonism.” In other words, depression no longer seems to be defined by an absence of pleasure—anhedonia—but rather by our inability to pursue anything other than pleasure itself. This is why we remain chained to our phones, reservoirs of low-cost artificial dopamine that allow us, “like a vitalist trick, to keep up the farce of life“ (2009).

Faced with an uncertain tomorrow, it is easy to be seduced by an eternal present. A present that, moreover, becomes a foreign land, as we grow increasingly dissociated from our wanderings through digital bubbles. Not only have we been robbed of the future, but dumb scrolling becomes the objective correlative of a present too painful to confront.

Yet, in a situation where the future seems like a matryoshka doll of closed doors and the present perpetually out of reach, how is it that we are more than ever inundated with a chain of novelties? Could it be that these are nothing more than some of those “vitalist tricks” mentioned earlier?

LOSING TRACK OF TIME

The pursuit of novelty—necessary to fuel the myth of unlimited growth—has thus produced a sense of exhaustion of the future. An impasse that seems to stem directly from the ability to access, with a single click, limitless reserves of the past. In other words, we have become victims of our own capacity to catalog. Suffocated by omniscient archives, we reduce our ability to act in the present.

On this point, Fredric Jameson—in his analysis of postmodernity—already observed how the novelties of his time were nothing but recombinations of things already seen. Similarly, music critic Simon Reynolds speaks of Retromania (2011), an obsession with the past that manifests itself, exemplarily, in pop phenomena, spokespeople for a retro style rather than a new wave.

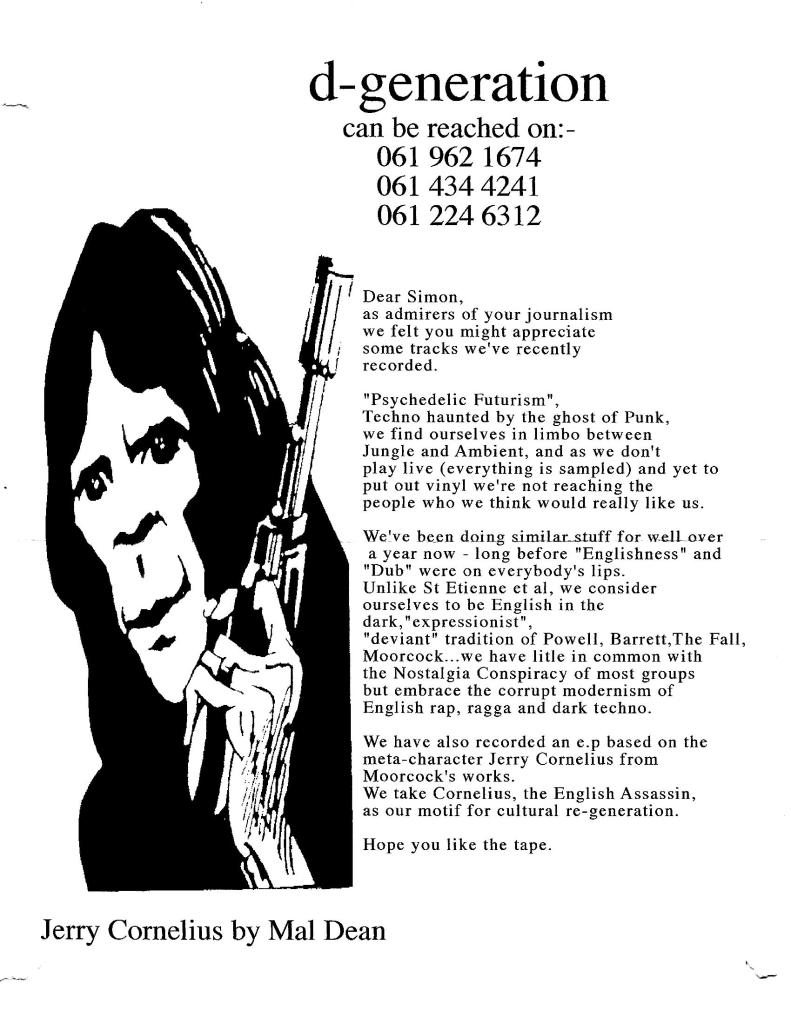

Against this “Conspiracy of Nostalgia”—as Fisher calls it in the letter he sent to critic Simon Reynolds for reviewing his youth band, D-Generation—the philosopher proposes melancholia. A disposition aimed not so much at the past, but rather at lost futures—those alternatives that, having ended up in some dead-end of the future or crushed under the weight of history, could still be reawakened through hauntology.

Borrowed from Derrida’s philosophy, Fisher understands the concept of “hauntology” as the cyclical return of lost futures. A formulation that shifts our gaze toward the doors of nearly-forgotten pasts—which, if finally reopened, could once again expand the horizon of the future. If nostalgia risks trapping entire generations in a “historical stiff neck”, then the only way forward is to unclog the path toward the future and reclaim full agency over the present.

CLAIMING THE FUTURE WITH POST- PUNK

Returning now to the letter to Reynolds, Fisher defines their band’s genre as: “techno haunted by the ghost of punk.”

In a scenario of systemic crisis like the present one, it can be particularly useful to nurture a sense of melancholy toward a cultural movement like post-punk. In the late 70s, young people, anguished by the Cold War and the possibility of nuclear conflict, held no expectations for the future beyond collapse. Yet, this attitude led them to master uncertainty, to dramatize it, and even to turn it into the catalyst for their propulsive innovation.

I believe that today—with the heightened critical perspective offered by temporal distance—we can look back to this moment to reclaim its strength. We can evoke the specters of its bold, dissident energy and, with them, reawaken the dormant class resentment. In doing so, we might finally reclaim the future, starting from the recognition of the urgency of the present.

Let us then stomp on the back of history, so that it may exhume from its body all those possibilities once believed to be extinguished but which, at any moment, could return to illuminate the reserve of the future.

LA MELANCOLIA POST-PUNK E IL FUTURO PERSO DI MARK FISHER

Che cosa succede quando si sgretola la promessa del futuro e il presente assume i contorni di un labirinto che percorriamo distratti? Quali sono gli effetti di un passato che, apparentemente illimitato, sembra soffocare la finestra del presente?

A queste e molte altre domande provò a rispondere il filosofo Mark Fisher (Regno Unito, 1968-2017) la cui lettura della storia, con i suoi disturbi e dei suoi sintomi, rappresenta un eccellente strumento per orientarsi nell’attualità.

Nel suo saggio principale, Realismo Capitalista (2009), il critico menziona spesso la lenta cancellazione del futuro (Franco Berardi) o la fine della storia (Francis Fukuyama). Espressioni claustrofobiche che comunicano il profondo senso di sconforto di fronte a un destino già scritto. Da qui l’idea immortalata nell’incipit: “è più facile immaginare la fine del mondo che la fine del capitalismo”, con cui Fisher apre la sua opera magna.

Il realismo inteso da Fisher è la soluzione migliore ai problemi contemporanei: cercare alternative non è altro che una perdita di tempo, una manifestazione di ingenuo utopismo. Davanti a questo furto d’immaginazione e di speranza, è facile comprendere il dilagante senso di perdita e turbamento.

LA CRISI MENTALE DEL REALISMO, TRA ANSIA E SOCIAL MEDIA

Le malattie mentali occupano uno spazio centrale nell’opera fisheriana. Il filosofo rivendica la necessità di analizzare più a fondo le cause dei disturbi generalmente considerati di “secondo livello”, come l’ansia. Fisher, che sperimentò in prima persona la morsa dell’ansia e della depressione, denuciava la responsabilità sociale del Capitalismo. Ansia e depressione sono reazioni umane e naturali di fronte alla devastazione del sistema. Siamo in balia di macchina che non si cura d’altro se non di ciò che la ingrassa; una macchina che fa leva sul bisogno umano di assuefazione

Schermi che ammaliano con il loro violento luccichio. Vortici di dati e caroselli di banalità che – zombificandoci – placano il nostro sconforto.

Il nostro rapporto morboso con la tecnologia e, soprattutto, con i social media ci rinchiude in quella che Fisher definisce edonia depressiva. In altre parole, la depressione non sembra più caratterizzarsi da assenza di piacere — anedonia — bensì proprio dalla nostra incapacità di rincorrere nient’altro che il piacere. Per questo rimaniamo incatenati ai nostri telefoni, riserve di dopamina artificiale a basso costo che permettono: “come un trucco vitalista di mantenere in piedi la farsa della vita” (2009).

Davanti ad un domani incerto, è facile lasciarsi sedurre da un eterno presente. Un presente che diventa una terra estranea, dissociati come siamo dal nostro vagabondare per ore in bolle digitali. Il dumb scrolling è il correlativo oggettivo di un presente troppo doloroso da affrontare.

PERDERE LA COGNIZIONE DEL TEMPO

In una situazione in cui il futuro sembra essere una matrioska di porte chiuse e il presente una X eternamente irraggiungibile, com’è possibile che veniamo più che mai sommersi da una catena di novità? Possibile che queste altro non siano se non uno di quei “trucchi vitalisti” prima menzionati?

La rincorsa alla novità, necessaria per alimentare il mito della crescita illimitata, ha prodotto una sensazione di esaurimento del futuro. Un’impasse che sembra derivare direttamente dalla possibilità di accedere – con un solo click – alle riserve illimitate e certe di passato. Siamo diventati, in altre parole, vittime della nostra stessa capacità di catalogare. Soffocati da archivi onniscienti, riduciamo la nostra capacità di agire nel presente e di plasmare il futuro.

Su questo punto, Fredric Jameson — nella sua analisi della postmodernità — osservava già come le novità del suo tempo non fossero altro che ricombinazioni di cose già viste. Analogamente, il critico musicale Simon Reynolds parla di Retromania (2011), un’ossessione per il passato che si manifesta nei fenomeni pop, portavoce di uno stile retrò piuttosto che di una new wave.

Contro questa “Cospirazione della Nostalgia” — come Fisher la definisce già nella missiva inviata al critico Reynolds per recensire la sua banda giovanile, D-generation — il filosofo parla di Melanconia. La Melanconia è un’inclinazione rivolta a futuri perduti, a quelle alternative che, finite in qualche vicolo cieco del futuro o schiacciate sotto una piega troppo pesante della storia, potrebbero essere rievocate tramite l’hauntology.

Mutuato dalla filosofia di Derrida, Fisher intende il concetto della ‘spettrologia’ come il ritorno ciclico di futuri perduti. Una formulazione che getta dunque lo sguardo sulle porte di passati quasi-dimenticati ma che, se finalmente dischiusi, sarebbero in grado di spalancare l’orizzonte del futuro. Se la nostalgia corre il rischio di intrappolare intere generazioni in un torcicollo storico, serve allora sgorgare l’orizzonte del futuro per tornare ad agire pienamente sull’oggi.

RIVENDICARE IL FUTURO CON IL POST PUNK

Tornando adesso alla missiva a Reynolds, Fisher vi definisce il genere della loro band come: “techno perseguitata dal fantasma del punk”.

Ora, in uno scenario di crisi sistemica come quello attuale, può risultare particolarmente utile alimentare la melanconia verso un movimento culturale come quello del post-punk. Sul finire degli anni Settanta, i giovani, angosciati dalla Guerra Fredda e da un possibile conflitto nucleare, non coltivavano nessuna aspettativa verso il futuro se non il collasso. Atteggiamento che li condusse tuttavia a padroneggiare l’incertezza, a drammatizzarla e a farne addirittura il catalizzatore della loro innovazione propulsiva.

Credo che oggi, con l’accresciuta capacità critica offerta dalla distanza temporale, possiamo rivolgerci a questo momento per recuperarne le forze. Evocare gli spettri della sua sfacciata energia dissidente e risvegliare, con essi, l’assopito risentimento di classe. Per rivendicare così finalmente il futuro, a partire dal riconoscimento dell’urgenza del presente.

Battiamo dunque i piedi sulla schiena della storia, affinché riesumino dal suo corpo tutte quelle possibilità credute spente ma che, da un momento all’altro, potrebbero tornare ad illuminare la riserva del futuro.

ARTICLE & TRANSLATION

by VIOLA AMICO

PH from the web