“Grimoire.” Just the sound of the word sends a shiver down the spine, as if something ancient were stirring in the air. For some, it conjures up images of witches, demons, and dusty leather-bound tomes. Others think of cryptic formulas and arcane symbols. But the allure of a grimoire goes far beyond gothic fantasy. More than a simple object, it’s a symbol—a vessel of hidden knowledge, a portal to what can’t be seen but can be felt. And today, somewhat unexpectedly, it’s beginning to speak again.

To understand why grimoires are resurfacing now—of all times—in this hyper-digital and disenchanted era, we have to go back to the beginning.

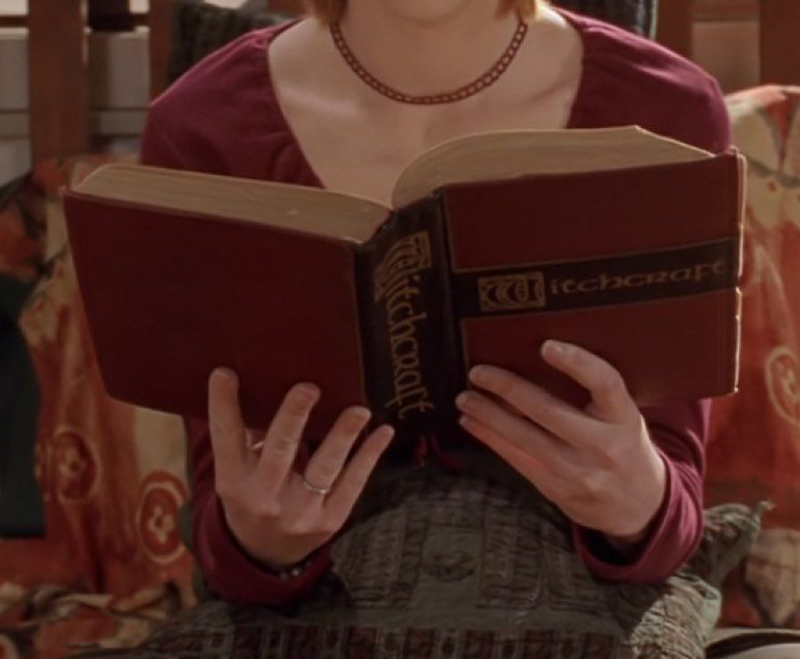

At its core, a grimoire is a book of magic. But don’t think of it as narrative or fictional. Grimoires were practical tools—manuals for those who studied the occult arts, astrology, herbalism, alchemy, or theurgy. Within their pages were spells, seals, prayers, invocations, planetary charts, lists of spiritual entities and instructions on how to summon them, heal, protect, or gain insight.

But if we stop at this technical definition, we miss the true essence of a grimoire. Because each one was also deeply personal. Often handwritten, passed down through generations, and evolving over time, a grimoire reflected the worldview of its creator. It was an attempt to bring order to the unknown. And from this desire to understand and interact with the mystery, the grimoire was born.

Some of the most well-known grimoires, like the Picatrix or the Key of Solomon, date back to the Middle Ages. But their roots reach further, into the magical texts of Hellenistic Egypt, Greco-Roman papyri, Babylonian rituals, and Jewish esoteric practices.

These books wove together astronomy and symbolism, natural medicine and religion, folk magic and high philosophy. They weren’t fringe—they lived in the folds of official knowledge, walking a fine line between the accepted and the forbidden. And it was precisely in this liminal space that grimoires found their power. A power that made them both sought after and feared.

During the Inquisition, owning a grimoire could be a death sentence. Many were burned alongside their authors. Yet grimoires survived—hidden by trusted hands, copied in secret, tucked away in monasteries, or passed down orally from initiate to initiate. Some remained in private libraries; others were disguised as religious or philosophical texts.

Magical knowledge never truly disappeared—it simply moved. From light to shadow, from public to private. And while the world changed, the grimoires endured. Silent, but still present. Waiting for a time when they could speak again. And that time, perhaps, has come. In recent years, grimoires have experienced an unexpected revival. Not just as historical artifacts or collector’s items, but as living tools. In a world that demands constant productivity and connection, many people feel the need to slow down, to reclaim ritual in daily life, to create sacred space in the ordinary.

In this sense, the grimoire answers a very modern spiritual need: to reconnect beauty and meaning, action and intention, introspection and creativity. It’s no longer just a book to read—it’s a book to write, to decorate, to inhabit. It’s an act of poetic resistance in a time that tends to flatten and standardize everything. But to be reborn, the grimoire had to transform.

IL RITORNO DEI GRIMORI

Grimorio. Basta pronunciare questa parola per avvertire un fremito, come se qualcosa di antico si muovesse nell’aria. C’è chi immagina subito streghe, demoni e polverosi libri rilegati in pelle; chi invece pensa a formule incomprensibili e simboli arcani. Ma il fascino di un grimorio va ben oltre l’immaginario gotico. È un simbolo, prima ancora che un oggetto. Un contenitore di conoscenze nascoste, un portale verso ciò che non si vede ma si intuisce. E che oggi, sorprendentemente, torna a parlare.

Per capire perché stia riemergendo proprio ora, in un’epoca ipertecnologica e disincantata, è necessario partire dall’inizio.

Un grimorio è un libro di magia. Ma non immaginare qualcosa di narrativo o romanzato. I grimori erano testi pratici: veri e propri manuali per chi si occupava di arti occulte, astrologia, erboristeria, alchimia o teurgia. Al loro interno si trovavano formule, sigilli, preghiere, invocazioni, tabelle planetarie, elenchi di entità spirituali e le modalità per evocarle, curare, proteggere, conoscere.

Ma se ci fermiamo a questa definizione tecnica, perdiamo il cuore del grimorio. Perché ogni grimorio era anche profondamente personale. Spesso scritto a mano, tramandato in famiglia, modificato nel tempo, rappresentava la visione del mondo di chi lo scriveva. Era un tentativo di mettere ordine nel mistero. Ed è proprio dal desiderio di comprendere e interagire con il mistero che nasce la loro origine.

Alcuni dei grimori più noti, come il Picatrix o la Clavicula Salomonis, risalgono al Medioevo, ma le loro radici affondano molto più indietro, nei testi magici dell’Egitto ellenistico, nei papiri greco- romani, nei rituali babilonesi e nelle pratiche esoteriche giudaiche.

Questi testi mescolavano sapere astronomico e simbolico, medicina naturale e religione, magia popolare e alta filosofia. Non erano marginali, ma si muovevano nelle pieghe del sapere ufficiale, in bilico tra la conoscenza accettata e quella condannata. Ed è proprio in questo spazio di confine che i grimori hanno trovato la loro forza. Una forza che li ha resi tanto ambiti quanto perseguitati.

Durante l’Inquisizione, possedere un grimorio poteva essere pericoloso. Molti vennero bruciati insieme ai loro autori. Eppure, i grimori hanno continuato a esistere, protetti da mani fidate, copiati a mano, nascosti nei monasteri o trasmessi oralmente da iniziato a iniziato. Alcuni sopravvissero nelle biblioteche private, altri vennero camuffati da testi religiosi o filosofici.

Il sapere magico non è mai scomparso del tutto: si è semplicemente spostato. Dalla luce all’ombra, dal pubblico al privato. E così, mentre il mondo cambiava, i grimori restavano. Silenziosi, ma presenti. Aspettando un tempo in cui tornare a parlare apertamente. E quel tempo, forse, è arrivato.

Negli ultimi anni, i grimori hanno conosciuto una nuova fioritura. Non tanto come testi storici o oggetti da collezione, ma come strumenti vivi. In un mondo che ci vuole efficienti e connessi, molte persone sentono il bisogno di rallentare, di creare rituali quotidiani, di ritrovare uno spazio sacro nella vita ordinaria.

Il grimorio, in questo senso, risponde a un’esigenza spirituale contemporanea: unire estetica e significato, gesto e intenzione, introspezione e creatività. Non è più solo un libro da leggere: è un oggetto da scrivere, decorare, abitare. È un atto di resistenza poetica in un’epoca che tende a semplificare e omologare. Ma per rinascere, ha dovuto trasformarsi.

Oggi, un grimorio può avere mille forme. Può essere un bullet journal decorato con simboli e colori, un diario delle fasi lunari, un taccuino con piante pressate, una raccolta di sogni, meditazioni e intenzioni. C’è chi lo usa per studiare astrologia, chi per accompagnare i cicli lunari, chi lo considera uno spazio creativo sacro. A volte è minimalista, altre è barocco e ricco di collage.

La cosa certa è che, anche nella sua forma moderna, il grimorio conserva la sua funzione originaria: dare forma all’invisibile. E oggi, anziché evocare spiriti, aiuta a evocare emozioni, visioni, parti di sé dimenticate.

Nel nostro tempo, un grimorio non è più un oggetto misterioso per pochi eletti. È un invito. A scrivere, disegnare, osservare. A rallentare. È un modo per riconnettersi a se stessi attraverso simboli, gesti, parole. Per molti, è anche un modo di rendere sacro ciò che sembra banale.

La magia non è scomparsa: ha solo cambiato forma. E forse oggi, il vero incantesimo è sedersi in silenzio con un foglio bianco davanti, e lasciare che qualcosa emerga. Un grimorio, dopotutto, è questo: una promessa di ascolto. Una pagina che custodisce ciò che ancora non riusciamo a dire, ma che abbiamo bisogno di scrivere.

ARTICLE & TRANSLATION

ALICE CIREGIA

@alice.healthcopy